Author: Bodytheology

not all storytelling is therapy

“While the telling of stories can be therapeutic, not all storytelling is therapy.” – Jacob

In this blog, I would like to sketch a few desiderata for narrative therapy flowing from the power of storytelling (https://bodytheology.co.za/2018/11/28/the-power-of-storytelling/ ). I have touched upon some of it in previous blogs and shall expound them further in 2019:

[desideratum/ plural noun: desiderata – something that is needed or wanted or required]

- We should explore what “deep listening” entails and how we protect ourselves from compassion fatigue.

- We should explore how language work in the body (of which the brain is part off) and enable clients to “find the words that work”. We still tend to divide brain and body, body and mind.

- We should explore the gap between experiences and language, the space or moment between what we experience before we try to put those happenings into words or narratives – we should find ways to explore the unsaid.

- IPNB (Interpersonal Neurobiology) refers to interpersonal attunement as the experience of a sense of emotional attunement with another attentive individual. I want to go further – as therapists (narrative or pastoral) it is not only an emotional attunement we experience with our clients. We form an “inter-embodied understanding” with the person sitting across us. We should explore what this means.

Then storytelling becomes more than just the telling of stories, but together we author a coherent narrative, “weaving their stories into our own stories”.

pain is stored in the body

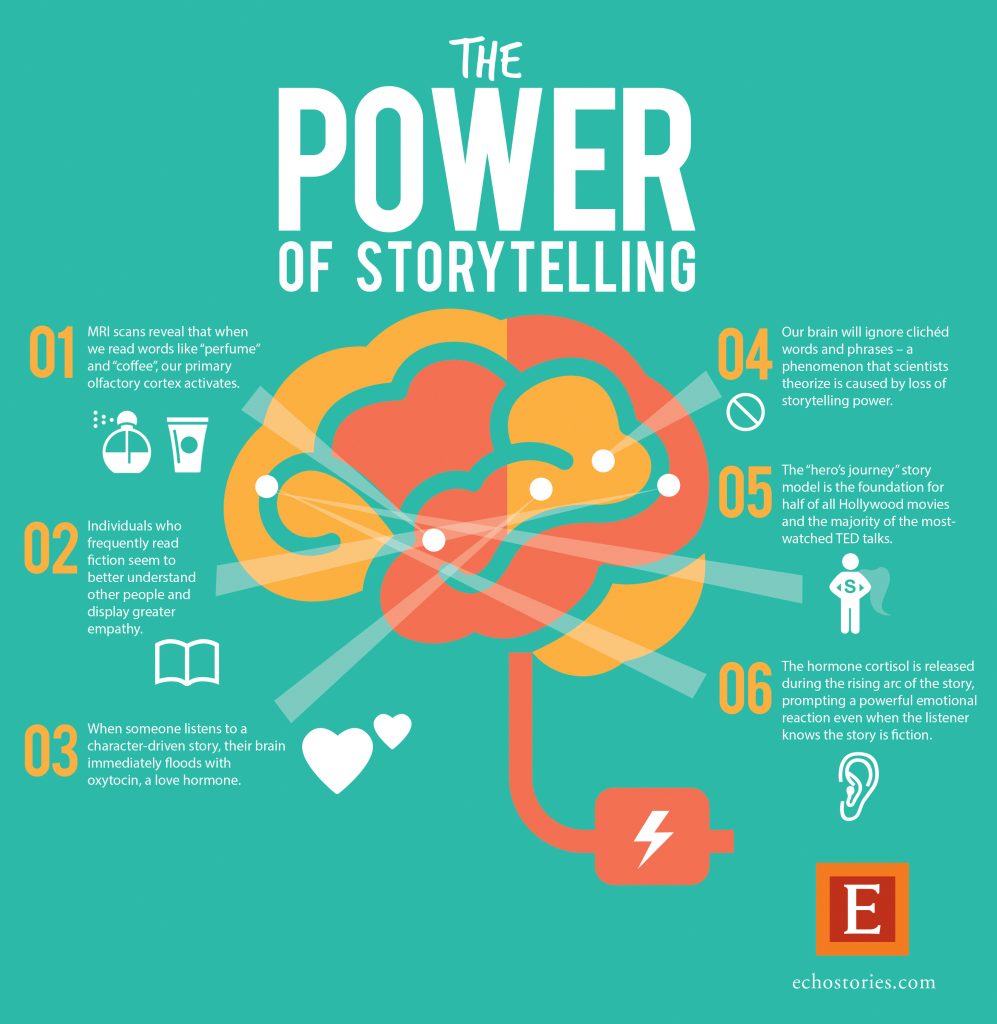

the power of storytelling

There are more compassionate ways of being in the world and it become possible when we relate to others face-to-face, voice-to-voice, and body-to-body. It is as simple as that. Relationships with others bring us in contact with that which transcends the ordinary. This is one way to reverse the erosion of empathy and to make empathy great again. It is as simple as that. (https://bodytheology.co.za/2018/11/22/make-empathy-great-again/ ) Through compassionate relationships, we can overcome the things that separate us and embrace the Otherness we fear. It is as simple as that.

It also happens through the telling of stories – and the deep listening to those stories.

There is a field of study called Interpersonal neurobiology (IPNB). It aims to paint a picture of human experiences and the dynamics of change across the lifespan by focussing on ways in which human beings are formed and transformed through relationships. It is especially interested in the processes by which neural systems shape human patterns of attachment and how these attachments shape neuron patterns. It looks at how relationships transform the architecture and functioning of the human brain. Louis Cozzolino, a key figure in IPNB defines it as “the study of how we attach and grow and interconnect throughout life” (Andrea Hollingsworth).

Empathy is derived from the German word “Einfühlung”, or “to feel into”. It is about the capacity to be affected by, and share in the state of another in such a way that we maintain self-awareness, even as we “feel into” the other’s experience. Sharing does not mean fusing with. Interpersonal attunement in IPNB refers to the experience of a sense of emotional attunement with another attentive individual. It is mindful awareness (intentional, nonjudgmental attentiveness to one’s own thoughts, feelings and bodily states in the moment), which has the possibility to change previous patterns of fear, inflexibility and reactivity to newly integrated patterns of calm, adaptability and balance. IPNB suggests that learning not to fear and learning to love are mutually conditioning neurobiological realities, and that relationships of safety and trust are integral to the emergence of both. Fear, also the fear of compassion, is primal and powerful and inversely related to compassion.

IPNB points to storytelling as a key means of neural regulation and integration. The hypothesis is that the practice of telling and listening to narratives became an evolutionary strategy to allow the brain to grow further in size and complexity. Research reveals strong links between mental health, emotional regulation, secure attachments, and coherent narratives. Cozzolino writes that narratives provided a tool for the brain to bringing together multiple functions from diverse neural networks for emotional and neural integration.

Storytelling holds the potential to raise us to greater levels of concern for the pain of others, and to stand in solidarity with others by weaving their stories into our own stories.

Note: Image designed by echostories.com

make empathy great again

I’ve been staring at this photo for a while now, each time it appears in my picture folder. And every time I read about Donald Trump and his “Make America Great!” crusade, I think of this photo. It is a brutal crusade. A quick search defines a crusade as either “a series of medieval military expeditions made by Europeans to recover the Holy Land from the Muslims in the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries” or“a vigorous campaign for political, social, or religious change”.

In Trump’s case it’s a potent mixture of both, an alchemy of fearmongering and hate enforced by state and social institutions to repel the Muslims (which includes Mexicans and other South American refugees, highly skilled professionals from Middle Eastern countries, climate change advocates, transgender people, paid prostitutes…and the list goes on). All this to brutally enforce a specific political ideology of greed, exclusion and macho-bullying with components of social engineering and religious condonation (https://bodytheology.co.za/2018/10/03/the-violence-of-words/ ).

So yes, perhaps I’m a bit angry. I’m angry to be a witness of a person using power as a blunt force instrument against the Other, smaller, gentler, more decent person at the cost of empathy, care and embracing each other’s humanity. In this process he exploits the fear, financial insecurity and feeling of insignificance of most of his followers. But it’s not only over there – it’s also right here. It’s been happening in the new South Africa, and brutally and crudely over decades of oppression and centuries of exploitation. There are many trampled bodies left floundering in its wake.

The erosion of empathy is not only the responsibility of the young. It’s not only technology which estranges us from “body-to body, face-to face and voice-to voice contact” (https://bodytheology.co.za/2018/11/15/the-erosion-of-empathy/ ). It’s also the result of political and religious ideologies enforced by foolish men (as in not acting with wisdom) keeping people apart. It is the effect of historical trauma passed on from one brutalised generation to the next, the “thousands of small stories still adrift in the sea of trauma”. It is the effect of diminishing networks and households of care as a result of migrant labour, poverty, but also rampant individualism (https://bodytheology.co.za/2018/10/17/ubuntu-and-the-body-as-narrative-principles/ ). And it is the effects of the power of certain types of men and their dominant and abusive masculinities on children, women and other men.

How do we reverse the erosion of empathy to make empathy great again? It definitely has to do with the exercise of power in political, social and religious structures, but somehow it starts with body- to body, face-to-face, voice-to voice contact – to overcome the things that separate us, to embrace the Otherness we fear.

the erosion of empathy

We do not leave our bodies behind when we enter cyberspace. You can re-create yourself as a sexy 20 year old, when the person behind the smartphone or laptop screen is in fact a 53 year old middle aged person, munching on a big bag of chips. The task to make meaning through the body you are still remains, even if we employ multiple identities to do this in the concrete everyday life world or a fantasy world created through social media and hi-tech computer games.

My concern for a quite a while has been that we are rearing a generation of young people whose ability to empathise is being diminished. Interaction with other people is more and more filtered through a screen and boundaries of the real and the imagined get blurred. Watching a video of someone being de-capitated by an extreme Islamist group (ISIS) is very much the same as obliterating your foe in a fierce battle in a computer game. If our ability to empathise is dependent on mirror- neurons in the brain (neurological responses to the experience of other individuals, “feeling” the experience second hand as a necessary condition for empathy), isn’t this slowly being eroded away the less we relate to others face-to-face, voice-to-voice and body-to-body?

In a recent article, psychology professor Jean Twenge from San Diego State University views smartphones and social media as raising an unhappy, compliant ‘iGen’ (the generation born in 1995 and later as the first generation to spend their entire adolescence in the age of the smartphone). “They spend a lot more time online, on social media and playing games, and they spend less time on non-screen activities like reading books, sleeping or seeing their friends in face-to-face interactions. By the age of 18, they are less likely to have a driver’s licence, to work in a paying job, to go out on dates, to drink alcohol or to go out without their parents compared to teens in previous generations. They are probably the safest generation in history and they like that idea of feeling safe”.

In an interview, prof Twenge said that “around 2011 and 2012, I started to see more sudden changes to teens, like big increases of teens feeling lonely or left out, or that they could not do anything right, that their life was not useful, which are classic symptoms of depression. Depressive symptoms have climbed 60% in just five years, with rates of self-harm like cutting (themselves) that have doubled or even tripled in girls. Teen suicide has doubled in a few years. Right at the time when smartphones became common, those mental health issues started to show up. We know, from decades of research, that getting enough sleep and seeing friends in person is a good recipe for mental health and that staring at a screen for many hours a day is not.”

So perhaps, my concern is not that far off when reading about these symptoms. But what is the wider impact on society of a generation that is loosing the ability to “feel into” others, a generation more-and more isolated from warm human touch?

Also see: https://ewn.co.za/2018/11/13/smartphones-raising-a-mentally-fragile-generation-says-academic

the art of loving

it’s late at night

actually

early tuesday morning

my mind is racing, streaming fragments of the day

an unsatisfactory meeting with colleagues at work

a therapy session with clients negotiating the boundaries of intimacy

impressions of walking the dog to the park

a whatsapp call early evening with my daughter in a far-off country

commuting in an overcrowded train from the city on her way back home

a dull ache in my lower back, shoulder muscles sore and tense

swiping through netflix

i stumble upon a delight

the art of loving

a polish film on the story of Michalina Wisłocka

gynecologist, sexologist, author of Sztuka kochania

verbatim The Art of Loving, in English boringly A Practical Guide to Marital Bliss

first guide in the 1970s to sexual life in communist countries, 7 million copies sold

no talk about sex with exaggeration or shy blushing

no judgement of people, or moralising over questionable choices

a straightforward story about a charismatic woman

taking on the patriarchal structures of the people’s republic and catholic church

benefiting her patients, paying for her choices with a ruined private life

but her body and soul connected into one, indivisible whole

i fall asleep, a smile on my face

Photo – Still from the movie Art of Love: The Story of Michalina Wislocka directed by Maria Sadowska, 2016. In the photo: Magdalena Boczarska and Eryk Lubos, photo: © Jarosław Sosiński / Watchout Productions

Also see: https://culture.pl/en/work/the-art-of-love-the-story-of-michalina-wislocka-maria-sadowska

sing canary sing

Sometimes my body reverberates with all the sensations from within, being bombarded with impressions of people and events. Last week provided ample opportunity to be overwhelmed.

I saw the film Kanarie (Afrikaans for Canary), described as “a coming-of-age musical war drama, set in South Africa in 1985, about a young boy who discovers how through hardship, camaraderie, first love, and the liberating freedom of music, the true self can be discovered”(www.kanariefilm.com ). The film itself is a form of purging that comes from storytelling, exploring the fragility and brutality of masculinities during Apartheid when the church, state and society did their utmost to uphold the ideology of racial superiority and the idea of a civilised, righteous people. What the film also does, is open up a space, especially on social media where people (mostly men – boys in the 1970s and 80s) can share snippets of their experiences during the so-called border war. This was however also a low-scale civil war fought in the townships against our own people, where your terrorist was my freedom fighter.

In the same week, I met Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela, professor in psychology and author of “A human being died that night”. In this book she recounts her interviews with Eugene de Kock, the notorious commanding officer of the apartheid death squads. She also served on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Human Rights Violations Committee. Now she is chair for Historical Trauma and Transformation at Stellenbosch University (www.sun.ac.za/english/faculty/arts/historical-trauma-transformation/overview) doing research on historical trauma, its expression in memory and its repercussions across generations. It is focused on the South African context, but it also speaks to questions worldwide of the transmission of traumatic memory in the aftermath of historical trauma, dealing with the past, and the possibility of breaking intergenerational cycles of historical trauma.

And this is why my body reverberates – deeply mindful of my own story in the grand narrative of power and oppression of subversive identities, be it political or sexual. And being acutely aware of the thousands of small stories still adrift in a sea of trauma. So – sing canary, sing.

Becoming withered versions of ourselves

We can become bone-tired.

Turn into withered versions of ourselves.

All of us, those in the office and those on the fields.

But those in the office, often the more privileged have the luxury of having tiredness labelled. We pathologise our exhaustion as chronic fatigue syndrome and call it burnout or yuppie flue. We become a psychological or psychiatric problem. For the majority, tiredness is just part of life – you come home, cook supper, get up in the early hours of the morning and commute to work. In-between you cry, dance, laugh and visit friends.

People and their bodies became raw material during the industrial revolution of the 18th century. Exhaustion was already shaped by society as an illness in 1869. Since then our bodies became part of the production line, our brain likened to a computer and when we are overloaded, the image is of a battery that needs to be recharged to function at optimal capacity and deliver the goods. We do not easily tolerate vulnerability.

I do not minimise the impact of extreme exhaustion, especially for those continuously exposed to the trauma of others. The effects are real, likened to Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder (STSD). But medication, withdrawal, self-care strategies and returning to the same treadmill only go so far. Lack of support and social isolation is a risk factor. There should be a shift from rampant individualism to collective care, to connection. For centuries humans lived in groups of 40-150 people. In the 1500s the average European family consisted of about 20 people whose lives were intimately connected on a daily basis. In the 1850s an average family consisted of 10 people living in close proximity. In the 1960s it was reduced to 5 people, and in the 21st century to 4 people with 26% living alone in some societies. Rampant individualism poses people without any relationships as healthier than those with many. This contradicts fundamental human biology: humans are social mammals that only survived because of deeply interconnected and interdependent human contact.

This is where Ubuntu as narrative principle comes in (https://bodytheology.co.za/2018/10/17/ubuntu-and-the-body-as-narrative-principles/). The quintessence is that one’s humanity is dependent upon one’s relationship with others. Our humanity is intertwined with our colleagues in the workplace and our family at home. We should care more. An ethic of care suggests that how we act in an organisation is inherently connected to who we are as parents, children, friends, and family members. It connects people’s work to their broader lives in ways that go beyond traditional ideas of how work and family impact each other. An ethic of care has the potential to explore all the dimensions of care and empathy in organisations. It’s not about recharging someone’s battery – it’s about restoring a person’s humanity.

St Irenaeus of Lyon growing up in Smyrna on the west coast of Turkey during the 2nd century AD, wrote that “The glory of God is the human person fully alive”. We owe it to ourselves to be fully alive, to flourish as we allow others to flourish.

Ubuntu and the body as narrative principles

We are nurtured into becoming more human. Somehow, and very obstinately I am convinced that the notion of Ubuntu is a profound illustration of that which make us more human, of that which connects us. I am also convinced that it can be used as a guiding principle in narrative therapy. This I’ve explored in my lectures around empathy, compassion fatigue, burnout and human flourishing.

The notion of Ubuntu is expressed in ancient African proverbs, for example, the Nguni saying which translates to “a person is a person through other persons”, the Xitsonga expression “one finger cannot pick up a grain”. The quintessence of these sayings is that one’s humanity (humanness) is dependent upon one’s relationship with others. In Desmond Tutu’s Ubuntu theology the focus is on reconciliation, the restoration of the humanity and dignity of the victims of violence, but also that of the perpetrators of violence. “Our humanity was intertwined”.

At the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), Desmond Tutu replied – “yes indeed, these people were guilty of monstrous, even diabolical, deeds on their own submission, but — and this was an important but — that did not turn them into monsters or demons. To have done so would mean that they could not be held morally responsible for their deeds. Monsters have no moral responsibility”. We always remain accountable for what we say and do.

The body repeatedly featured in narratives at the TRC. The corpse or remains of the victims of apartheid became the “privileged site of intersection”. The “visual core” of the TRC was the appeal of witnesses to bodily violations. Victims’ bodies were violated – “descriptions, representations and conflicts around bodies in various states of mutilation, dismemberment, and internment within the terror of the past”. Family members repeatedly pleaded for the remains or body parts of their loved ones, “making their visibility, recovery and repossession a metaphor for the settlement of the past of apartheid” (L. Bethlehem)

For the sociologist Didier Fassin history is not simply a sum of different narratives, but “it is also what is inscribed within our bodies and makes us think and act as we do”. The body is not just a manifestation of a person’s presence in the world, but it is also a site where the past has left its mark or as he puts it “the body is a presence unto oneself and unto the world, embedded in a history that is both individual and collective: the trajectory of a life and the experience of a group”. This is a description of Ubuntu.

During the TRC the exposure of the scar in public also became an act of purification and a purging of the social body. The surface of the body became a site of memory during the TRC hearings. The sight of the violated body allowed the body to be “stabilised as the site of memory” (Bethlehem). The pain of the body is shared. This is the idea of the body as narrative.

The spirit of Ubuntu belongs to all of us, but I would appeal for a deep sensitivity to the experiences of brutalised people in South Africa and what they experienced in their bodies for centuries when evoking “the spirit of Ubuntu” in law, theology (Ubuntu based on human dignity, fellow-humanity, human interconnectedness and restorative justice) and in narrative therapy.