He slowly made his way down the stairs inside the hotel, eyes curious, making a few joking remarks. He was tired from travelling, but his small body diffused energy into the larger room where he engaged with us.

And then I noticed his hands.

I met Archbishop Desmond Tutu a few years ago in the lakeside town of Vreeland in the Netherlands. It was a late afternoon in early spring. As he sat down beside me to sign the cover page of my book/ thesis, he was clinging the pen with his left hand, his right hand lying limp, then swiftly he wrote a few words.

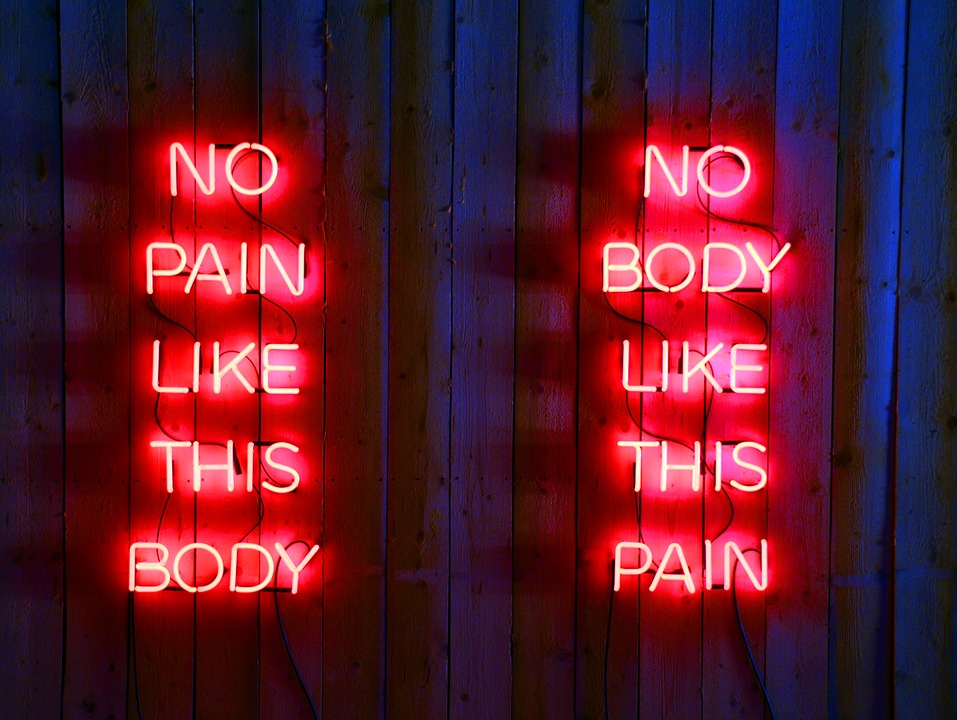

Later I wondered how his body influenced his fight for the underdog and oppressed. As a young child he burnt his body lying too close to a coal stove trying to stay warm; polio atrophied his right hand and one leg and later he contracted TB. Our words are intimately connected to our bodies. If language and the body is an ongoing process, then the body and words of Tutu is a witness of this close connection.

The theologian Nancey Murphy refers to the concept of bodily identity to explain that a person’s identity will only be understood in terms of the person’s own body. This opens a parallel line of thought to that of James Nelson (that faith can only be received in dependence of a person’s bodily experiences), namely that a person’s words of theology, and even words of counselling or therapy are closely related to his/her bodily identity.

With a finger wagging, Tutu scolded politicians; with gnarled hands holding his head, he cried after hearing the harrowing stories of torture victims; with his purple cloak trailing behind him, he led marches with other community activists against the brutality of Apartheid. He and Simeon Nkoane came across a crowd of mourners busy beating and kicking a man suspected of being a police informer. The man was doused with petrol, and as the crowd of youngsters prepared to throw him into the wreck of his burning car, the two of them waded into the crowd, jostling with the people. Reaching the centre of the crowd, the bleeding victim clung to Tutu’s legs and after pleading with the youths, they pulled the man out of the crowd and into a car.

With hands wringing in anguish, he spoke out against the violent attacks on foreigners, the corrective rape of lesbians, reprimanding Ugandan lawmakers that their anti-homosexuality bill is “reminiscent of what we experienced under Apartheid and what Jews experienced at the hands of Nazis”.

This week I sat listening to the eloquent and fiery words of speakers at the 8th Desmond Tutu International Peace lecture, but his chair was empty, watching the event from hospital. His body is withdrawing, his words are drying up.

But look at those hands.